Leading and learning in team coaching

5th July 2017

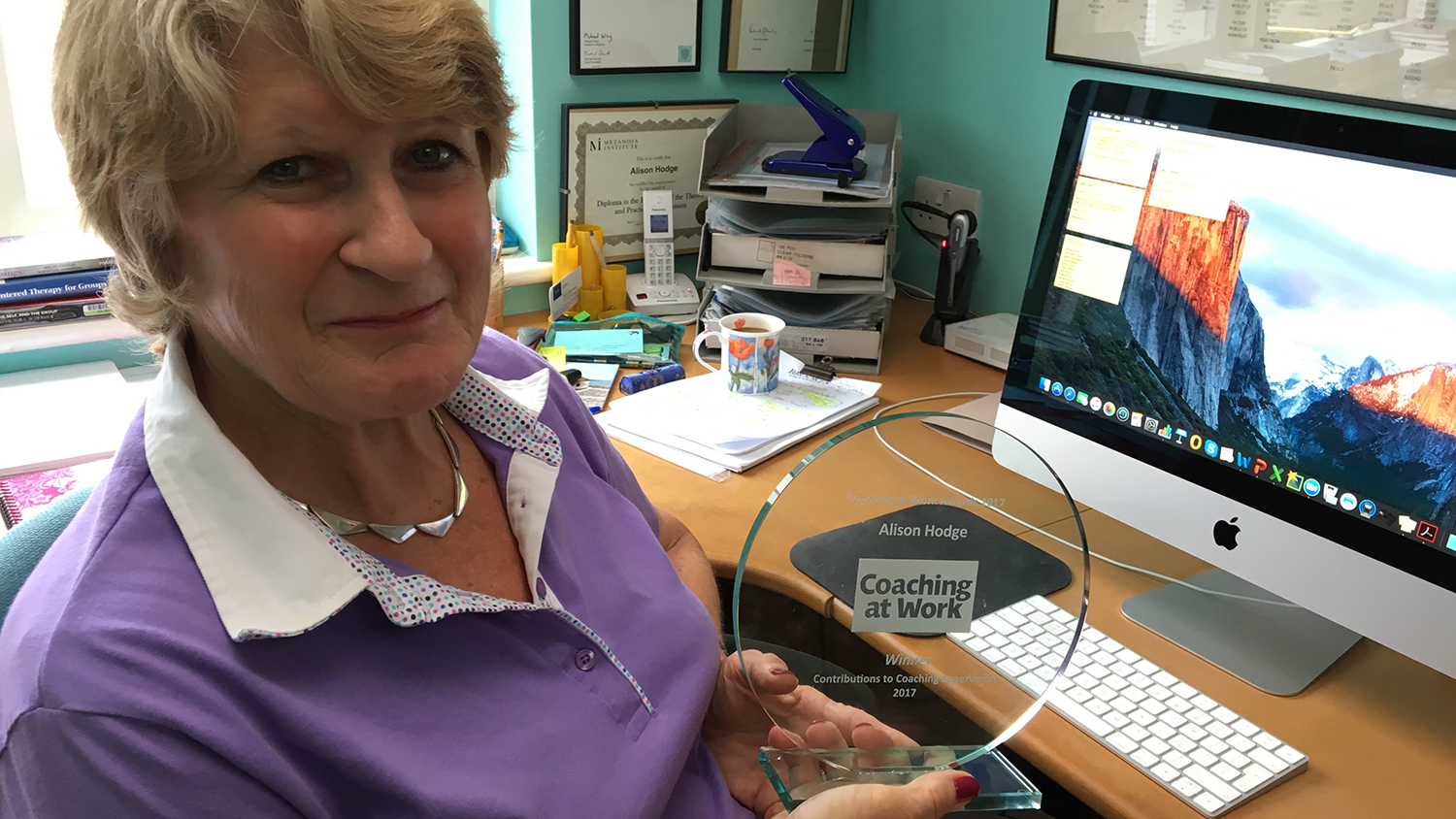

Contributing to coaching supervision

21st July 2017The art of the ending

In my experience as a coaching supervisor, endings have given me more pause for thought and more professional challenge than almost anything else. I’ve found there are at least three different endings. The first and most satisfying ending goes like this: ‘Let’s agree it’s time to end our work. You go with my blessing, I go with your blessing.’ This kind of mutually agreed ending is explicit: we talk about it, we plan it, and we do it. In my experience, this has been the norm and is usually when we both sense that the client needs a fresh set of eyes, new perspectives, or is developing interests that are beyond our work together.

A second sort of ending comes when a client disappears. The client might agree they’re going to have sessions, but then doesn’t fulfil them, and doesn’t respond to calls or emails. The relationship simply fades out in an unended ending, with no goodbye, nothing said, but just an open-ended silence. When that happens, you need to manage yourself very differently when compared with an ending where you are actively involved as a co-creator – or if indeed you as coach or supervisor have initiated the ending.

But the third kind of ending, and the one I want to reflect on here, comes about when there is a rupture in the relationship, and I need to initiate the ending from my side, hard though that is.

This can happen for a number of reasons. We might have reached a point where there is an accumulation of things going wrong which I haven’t had the courage to raise before, and which feel almost too late to raise now. This presents me, as the coach or supervisor, with an almost impossible choice. Do I withhold my discomfort at the way the work is going, and therefore in a sense betray an important part of the work, which is to model a truthful client relationship; or do I share my thoughts completely, which can lead to shock, confrontation and fireworks, with my client asking, ‘Where has this come from?’

I’ve discovered through painful experience that raising something that is awkward or frustrating, or which seems appropriate to raise because it may be playing out in the client’s practice, can lead to a rupture in the relationship. How we bring ourselves back from the rupture, if we choose to work with it, is very challenging and can result in great learning and a deepening of the relationship, and thus the work. And conversely, if I decide I can’t work with the rupture (or even, I don’t want to work with it) because it feels irrevocable, that is also very challenging. I’ve reluctantly had to face the fact that occasionally some endings aren’t, ‘Well, it’s been absolutely fabulous and I’ve loved working with you and I wish you well.’

Several pieces of learning have come home to me as I’ve faced these (what feel like) ‘damned if I do and damned if I don’t’ situations. One of them is about judgment, and another about the importance of timely sharing.

I once asked my supervisor, ‘How do you know when it’s ok or best to tell a client that you don’t want to work with them anymore?’ She said, ‘When you find you’re being too judgmental.’ So if I find that I can’t park my judge, and if my judge is coming into the work, then it’s time for me to go. That needs to be done respectfully, and not from a place of judgment. Initiating the ending in this case is in the client’s best interests, because if I’m feeling critical and judgmental, I’m not able to do my best work for them, and I’m not serving them well. I then need to let them go and allow them to explore another avenue.

I’ve also learned the importance of raising issues of concern immediately, and not holding onto them. If I raise difficult issues as soon as I notice them, my client might choose to end our relationship, but there is also the possibility that we can focus on the issues themselves and do good work together.

But if I leave the issues too long before sharing them, maybe taking them to my own supervision, they become an area we can’t talk about, and so they become unresolvable. In one theoretical model, taken from transactional analysis, I’ve been ‘stamp collecting’. I’ve been collecting stamps: You’ve done this wrong, and you’ve done that wrong, and finally I tell you what you’ve really done wrong, and all the stamps are revealed in one go. When that happens, it’s a terrible shock and it comes out in a very heavy way.

When we’re working with our clients, we rightly have our primary focus on the needs of the client. But I’ve also come to understand better that we need to attend to our own needs in the relationship. So while our attention is on attending to the needs of our client, if our own needs are being completely neglected, then again, we will not do our best work. How to balance these difficult opposites, and how to make the best endings we can, is part of our journey towards maturity as coaches and supervisors.

Reading that may be of interest

Good Enough Endings, Jill Salberg (editor)

Endings and Beginnings, Herbert J Schlesinger

Photo: Marcel